Claude Debussy – Color, Shapes and Proportions in La Mer (1909) and Other Works

Theories that assert Debussy’s intentional use of mathematical proportions in his works remain as mere speculations for many reasons. Works like La Mer and Estampes show distinctive structural attributes that suggest Debussy’s unequivocal use of mathematical ratios such as the Golden Section and the Fibonacci series. However, those compositions are not outright regarding the intentional or intuitive approach by the composer. These two systems of balance and proportion are pillars of the French Symbolist movement with which Debussy was very much associated towards the end of his student days. At this time, the composer spent more time among writers and painters than with fellow musicians.[1]

As a reaction against naturalism and realism, symbolism was among the anti-idealistic movements, which attempted to capture reality in its rough distinctiveness, and to elevate the humble and the ordinary over the ideal. Symbolism began with that reaction, favoring spirituality, the imagination and dreams.

Symbolist poets believed that art should aim to capture more absolute truths, which could only be accessed by indirect methods. Thus, they wrote in a highly metaphorical and suggestive manner, endowing particular images or objects with symbolic meaning. In the symbolists’ Manifesto, Jean Moréas, who published the document in 1886, proclaimed that symbolism was adverse to “plain meanings, declamations, false sentimentality and matter-of-fact description”, and that its goal instead was to “clothe [sic] the ideal in a perceptible form whose goal was not in itself, but whose sole purpose was to express the ideal”. [2]

They conceived the physical world as a collection of symbols, a language that needed to be deciphered by the spectator, where nothing has a plain meaning, everything evokes an deeper image, a metaphor. The Symbolist influence on Debussy is palpable, and of course Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune was inspired by Mallarmé’s poem L’après-midi d’un faune.

Those principles also influenced Debussy’s musical perception, where the architectural design of a work and its expressivity were inseparably bound. Every note had a meaning with an enormous expressive potential. In his review on Paul Dukas’ Piano Concerto from 1901, Debussy writes: “[…] you could say that the emotions themselves are a structural force, for the piece evokes a beauty comparable to the most perfect lines found in architecture.”[3]

“Music is a series of perceptible surfaces created to represent esoteric affinities, which Symbolists used to evoke their primordial ideals.” [4] In Debussy, sounds and their succession in time are indirect methods that conceal deeper meanings.

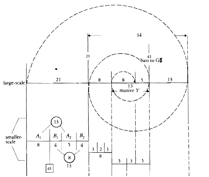

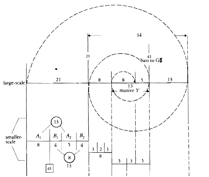

Spirals are present La Mer as a formal device that the composer utilizes in order to revisit certain material from the past that, and at the same time, transform it into new musical ideas that continue to develop in the same fashion. In this work, Debussy reveals his natural tendency towards repeated visits to the same musical territory, a characteristic fixation upon specific sounds, patterns, textures, harmonic structures, sonorities, even absolute pitches and melodic fragments, resulting in what we may call aural images. “One comes to feel that Debussy’s aural images are psychological links between certain works of his; they are signs of his unremitting perfectionism, in that, always doubting his own accomplishment, he may have attempted to pursue some forever-elusive musical idea by resurrecting it in another work turning his whole compositional output into a spiral.”[5]

Musical proportions and numerical experiences could have also come to Debussy through his Baudelaire readings, especially his essay Du vin et du hachish in which the poet describes a particularly vivid experience of music as numbers, intimately related to La Mer’s spiraled construction.

Figure 1. Spiraled form of La Mer according to Howat.

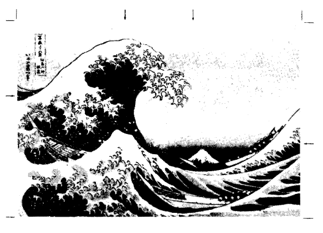

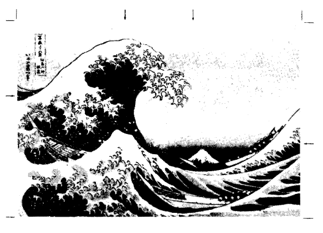

The first edition of La Mer appeared with a reproduction on the cover, at Debussy’s request, from Katsushika Hokusaki’s print The hollow of the wave off Kanagawa, a copy of which also hung on Debussy’s study wall. The dominating motive of the print is the wave, whose lower outline curves in logarithmic spiral, admittedly broader than Debussy’s variety. In addition, the golden section divisions indicated around the picture shows how close the composition comes to overall GS, especially if we consider the upper extremity of the wave, the side of its lower curve, and the top of Mount Fuji.[6] Those curves and extreme points of the waves are actual mathematical functions (if x and y axis are added, for example) that Debussy transplanted into form and the development of his musical ideas. A similar concept of translations of functions into music will be seen later on in this chapter, in the section about Xennakis.

Figure 2. Katsushika Hokusaki’s The hollow of the wave off Kanagawa.

“Despite those facts, none of Debussy’s surviving manuscripts contain any signs of numerical calculations concerning structure. This, however, is inconclusive, and also not surprising. Most of these manuscripts are the final copies given to the engraver, an artist as meticulous as Debussy was over the visual presentation of his scores, both manuscript and printed, would hardly have been so unprofessional as to deliver his finished product with scaffolding still attached. In any case, these final copies are mostly third or fourth drafts of the works concerned, by which stage their forms would be well established. Apart from these final copies, only a very small number of sketches have survived. Debussy is known to have destroyed the large majority of his sketches, and, while that proves neither side of the question, it could be conjectured that the few sketches which remain are those that divulge no secrets […] No firm conclusion can be drawn from the above.”[7]

Debussy was deeply aware of the numerical connotations of music composition, but it is still uncertain if he used them intentionally or not. “Music is a mysterious mathematical process whose elements are a part of infinity”.[8]

“In addition to that, it can be said that Debussy was completely unaware of his proportional systems. His subconscious judgment was responsible for organizing them with such precise logic and he would later have had to completely avoid the possibility of such occurrences in his later works.”[9] That awareness is confirmed if we compare the similar use of proportional schemes that appear in La Mer and La Cathédrale Engloutie two works that are considerably distant in Debussy’s career.

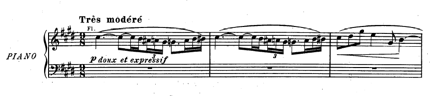

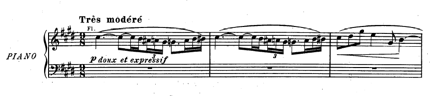

Additionally, the use of a center of resonance as a compositional device is another example of Debussy’s reinterpretation of his ideas throughout his production output. His Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune from 1895 (one of his most remarkable early works) undoubtedly circles around the pitch class C#; L’isle joyeuse, from 1905 (from his middle period), recurrently plays around the initial pitch class C#; Syrinx from 1913 (in his late period) is, for the most part, constructed around the initial pitch class Bb. These three works have a very similar initial harmonic and gestural structure and spanned throughout all Debussy’s compositional periods. This conceptual material seems to be revisited and reinterpreted, exemplifying Debussy’s natural tendency towards self-recycling. This arabesque ornamentation around a given pitch class is one of Debussy’s trademarks.

Figure 3. Measures 1-3 from Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune.

Similarly, the idea of Debussy using such scientific means of formal regulation (consciously or not) is quite incompatible with his known distaste for musical formulas, which at the same time were conceptual examples of “plain meanings”, quite unwelcome among the Symbolists. Literally, a formula is a prescribed method, convention or recipe, nothing metaphoric – a definition applicable to such construction as fugue, sonata form and so forth.[10] Debussy desired to evoke images and spirituality through his music and these self-explanatory processes were not a suitable tool.

Figure 4. Measures 1- 2 from L’isle joyeuse.

Figure 5. Measures 1- 2 from Syrinx.

Even though Debussy’s search for perfection in his scores is documented in some of his letters where he specifically expresses concern about golden section proportions. In a letter of August 1903 from Debussy to his publisher Jacques Durand, returning the corrected proofs of the Estampes, Debussy writes:

“You’ll see, on page 8 of ‘Jardins sous la pluie’, that there’s a bar missing – my mistake, besides, as it’s not in the manuscript. However, it’s necessary, as regards number; the divine number, as Plato and Mlle Liane de Pougy would say, each admittedly for different reasons”.[11]

The difference in proportion between the final score and the Sibley manuscript of De l’aube a midi sur la mer makes clear that the music was not composed to fit rigid plans impervious to any subsequent modification.

“If Debussy was applying GS consciously, the plans could evidently be remodeled according to other musical demands, many of which may have been primarily instinctive ones, however consciously carried out and perfected eventually. The point again is that Debussy would never have set his intellect on the rampage without simultaneously applying his intuitive judgment. If alternatively, he was completely unconscious of the proportions just seen, we are left with awkward logic. This is because the Sibley manuscript, even in its final state, does not have overall GS coherence and the final score has. This would mean, therefore, that Debussy’s proportional intuition failed him entirely with the large-scale dimensions in the Sibley manuscript, and then suddenly brought the form to virtually maximum accuracy in one fell swoop […] involving a changed tempo relationship that happily provided exactly the necessary dimensional adjustment.”[12]

Ray Howat has traced Debussy’s use of mathematical proportions in detail. Even though, few analyses of Debussy’s music consider dynamic shape at all, and those that do, tend to focus only on isolated aspects such as the principal climatic point of a work.[13] Nevertheless dynamics are a vital structural element of Debussy’s mature music. The tidal flow of swelling intensities of the dynamics – specifically in works like La Mer – reveals a novel programmatic method with an outstanding dramatic outcome. The tides, undulations of the waves, the wind and its shape, are metaphorically symbolized through the dynamic structure of the work which evokes particular states of mind and aural images that invite the listener to decipher them. As a vital component for the completion of Debussy’s music – the listener is constantly challenged to resolve aural puzzles. What is given appears to be incomplete; the symbols need the spectator to become meaningful. “In ‘Reflets dans l’eau’ the composer evokes the concentric propagation of sound waves, not only are many of the sequences […] visibly reflected round some central musical turning point; but also their reflected portions (or images) tend to be compressed in size, giving an effect of refraction – another aspect of reflection (or deflection) in water.”[14]

Somehow anticipating Le Corbusier, Debussy was also bound to the intrinsic properties of sound explained by Pythagoras and their numerical implications. Le Corbusier used the Pythagorean theory in order to justify his own set of ideas in which he desires to import the universality of the proportions of the individual components (harmonics) of a given sound into a model for architectural design not based on the properties of sound but on the human figure and its scope. On the other hand, Debussy finds a more poetic interpretation of the ancient theory: “[…] the old Pythagorean theory that music should be reduced to a combination of numbers: it is the ‘arithmetic of sound’ just as optics is the ‘geometry of light’.”[15]

Interestingly, his use of proportions never becomes formulaic, as it is never used in the same way twice. The similarities between Debussy’s pieces are always offset by a sharp contrast. In Debussy, the presence of spirals is always recurrent.

References:

[1] Ray Howat, “Debussy in proportion. A musical analysis”, (1983), 163.

[2] Jean Moreas, “Symbolist Manifiesto”, (1886).

[3] Ray Howat, Ibid. 173.

[4] Jean Moreas, Ibid.

[5] Mark De Voto, “Debussy and the Veil of Tonality”, (2004), 24.

[6] Ray Howat, Ibid. 178.

[7] Ray Howat, Ibid. 6.

[8] Ray Howat, Ibid. 171. Debussy (1977), 199.

[9] Ray Howat, Ibid. 162.

[10] Ray Howat, Ibid. 9.

[11] Ray Howat, Ibid. 7.

[12] Ray Howat, Ibid. 91.

[13] Ray Howat, Ibid. 12.

[14] Ray Howat, Ibid. 28.

[15] Ray Howat, Ibid. 171. Debussy (1977), 255.